The Ocean's Dirty Little Secret: 50 Years Since the Great Pacific Garbage Patch Discovery

In 1973, scientists announced their concerns for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Now, the 1.6 million km patch is disrupting life.

50 years ago, scientists on an oceanographic voyage in the Central Northern Pacific expressed concerns about 'the number of manmade objects littering the ocean surface.'

An article from ScienceNews on February 10, 1973 states "Even though they were 600 miles away from the nearest major civilization (Hawaii) and far off major shipping lanes, they recorded 53 man-made objects in 8.2 hours on viewing. More than half were plastic. They go on to compute that there are between 5 million and 35 million plastic bottles adrift in the North Pacific."

Setting Sail Into a Plastic Sea - article link.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

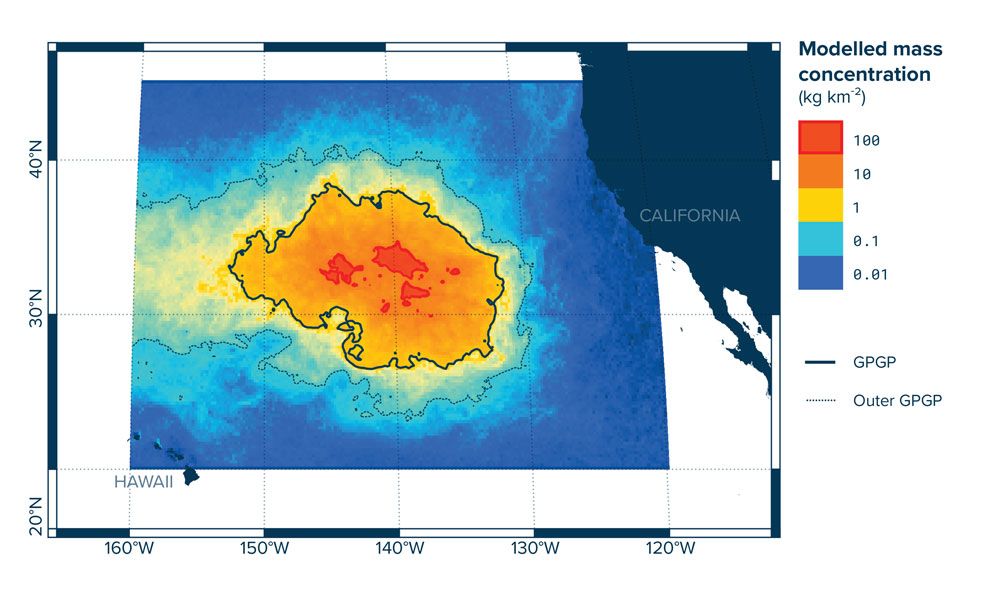

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, or the Pacific Trash Vortex, spans the length of the western coast of North America to Japan. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch consists of two separate garbage patches - the Western Garbage Patch near Japan and the Eastern Garbage Patch located between Hawaii and California. These two are linked with the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone. In this zone, warm water from the South Pacific meets the cold water from the Arctic, creating a 'highway' that moves debris between the patches.

The amount of debris accumulates quickly because most of it is not biodegradable. These patches aren't contained with a lot of large plastic, but more smaller microplastics. Microplastics can't always be seen with the naked eye. Even satellite imagery doesn't pick up the garbage patches. The microplastics make the patch look like cloudy, dirty water. It's filled with microplastics and other larger items like clothing, shoes, fishing nets, etc. Oceanographers also believe that the garbage patch may be an underwater trash heap - as 70% of marine debris sinks to the bottom of the ocean. Because of this, no one knows exactly how much trash makes up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

The Dirty Details

80% of plastic comes from land-based sources, and the other 20% comes from marine sources like boats. Because of plastics' low cost, it is being used more in consumer products. But it doesn't break down. Instead it breaks down into smaller pieces, and it begins accumulating more and more. The sun also breaks these down even more through a process called photodegradation. It's assumed that most debris comes from plastic bags, bottle caps, plastic water bottles, and Styrofoam cups. Because of its location, no country will take responsibility or provide funding for cleaning up the patch.

The approximate size of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is around 1.6 million square kilometers, or 994,193.9076 square miles. This would be twice the size of Texas or three times the size of France. The mass of the patch is approximately 80,000 tons. This is thought to be between 4-16 times more than previously thought. A total of 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic are estimated to be floating within the patch. This would account for around 250 pieces of plastic for every human on Earth. 1.8 is also estimated to be a mid value range. Actual values could be anywhere between 1.1 million or 3.6 million.

Scientists are now seeing evidence of the marine debris disrupting ecosystems. Floating at the surface of the garbage patch is 180 times more debris than marine life. Larger pieces can be mistaken for food, smaller animals can become trapped or entangled in the pieces, and the chemical breakdown of plastics into nearby water can become deadly for animals. And this in hand affects humans as well.

Bioaccumulation is a process where plastics consumed by marine life are absorbed into the body after consumption. As the feeder becomes the prey, those chemicals will then be absorbed into humans. The same plastic that affects marine life could affect humans as well. In hand, this affects the economy, with annual economic costs due to marine plastic are between $6-19 billion. It has impacts on tourism, fisheries, and governmental clean ups. Scientists hope that with time, we can continue cleaning the garbage patch and make the environment better for marine life who live there. But it's a collaboration across the globe and can't be done with one person alone. Maybe in the next 50 years, we'll see it shrinking instead of growing.